Introduction

In the Elizabethan period, everyone went to the theatre: commoners stood at ground level, while the upper classes sat in the balconies. Despite this separation, Shakespeare’s words were intended for all classes. His words did not require the viewer to be educated or even literate, but instead expected an understanding of shared human experience. By contrast, modern day Shakespeare is an icon of high literate culture, supposedly reserved only for the well educated and those that can afford theatre tickets.

In the Elizabethan period, everyone went to the theatre: commoners stood at ground level, while the upper classes sat in the balconies. Despite this separation, Shakespeare’s words were intended for all classes. His words did not require the viewer to be educated or even literate, but instead expected an understanding of shared human experience. By contrast, modern day Shakespeare is an icon of high literate culture, supposedly reserved only for the well educated and those that can afford theatre tickets.

Tongues in Trees, an audio installation by multimedia artist Dawn Matheson uses the medium of interventionist art to create a Shakespearean performance space for adults struggling with literacy due to learning disabilities–or a limited access to education because of troubled or low income histories. When approached with the project, only two of the participants had any past experience with Shakespeare. Nonetheless, each performer found and learned a monologue that personally related to their struggles and life experiences. These monologues were recorded and then, through an audio system set in trees outside the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, triggered by passers-by through the use of motion detectors hidden in front of the gallery. Tongues in Trees self-consciously refutes modernist notions of elite ownership that attach to Shakespeare and reinvents the relevance of Shakespeare to a wide audience regardless of class, educational standing, or ability.

Introduction

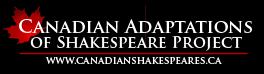

The L.W. Conolly Theatre Archives hosted at the University of Guelph represent the largest archival theatre holdings in Canada. A significant portion of these archives is devoted to Shakespearean productions and adaptations. The primary focus of the collection has been contemporary Ontario theatre, and today most major Ontario theatres are represented, as are a number of prominent individual theatre artists, including playwrights, directors, designers and actors. The L. W. Conolly archives are a testament to the rich history of movement of productions, actors, and playwrights across provincial and national borders, a movement also documented in the archives’ holdings.

The L.W. Conolly Theatre Archives hosted at the University of Guelph represent the largest archival theatre holdings in Canada. A significant portion of these archives is devoted to Shakespearean productions and adaptations. The primary focus of the collection has been contemporary Ontario theatre, and today most major Ontario theatres are represented, as are a number of prominent individual theatre artists, including playwrights, directors, designers and actors. The L. W. Conolly archives are a testament to the rich history of movement of productions, actors, and playwrights across provincial and national borders, a movement also documented in the archives’ holdings.

The L.W. Conolly Theatre Archives are a major resource for scholars around the world, and include collections of rare materials from William Hutt, the Canadian Players, the Stratford Festival and Tony Van Bridge, to name only a few. These collections include a wide array of documents and objects such as house programs, performance scripts, set models, posters, technical drawings, production photographs, costume designs, personal correspondence, and theatre props. Importantly, the collections showcase the ephemeral nature of theatrical performance and the necessary technical and artistic contexts that make theatre possible. And, of course, the archives illustrate the rich and varied contributions of individual artists and theatre companies, and display the evolution of theatrical culture in Canada. Though there are many strands of information in the archives, one important one relates to Shakespearean performances in Canada, providing further testament to Canada’s extraordinary relationship with Shakespeare, and how that relationship has permeated Canadian theatrical culture as a whole.

Introduction

The evolution of portraiture and what constitutes a portrait, and how portraits hold the ability to engage their audience in a discourse on identity and narrative is explored within this gallery on the Bard in Contemporary Portraiture. Within the Shakespeare Made in Canada exhibit this gallery was intended to showcase works specifically commissioned with Shakespeare in mind, and others that were made for a completely different purpose. The ability to see Shakespearean characters and tropes within the non-commissioned pieces attests to the pervasiveness of Shakespeare’s writings as markers of shared cultural experiences. Notable examples include Jean-Paul Tousignant’s Nathan and Erin, whose wide eyed vulnerability and diary-like scrawling suggest a modern Romeo and Juliet, and Shelly Niro’s representation of storytelling and mythology in Ghost, representative perhaps of patriarchal ghosts that haunt Hamlet.

The evolution of portraiture and what constitutes a portrait, and how portraits hold the ability to engage their audience in a discourse on identity and narrative is explored within this gallery on the Bard in Contemporary Portraiture. Within the Shakespeare Made in Canada exhibit this gallery was intended to showcase works specifically commissioned with Shakespeare in mind, and others that were made for a completely different purpose. The ability to see Shakespearean characters and tropes within the non-commissioned pieces attests to the pervasiveness of Shakespeare’s writings as markers of shared cultural experiences. Notable examples include Jean-Paul Tousignant’s Nathan and Erin, whose wide eyed vulnerability and diary-like scrawling suggest a modern Romeo and Juliet, and Shelly Niro’s representation of storytelling and mythology in Ghost, representative perhaps of patriarchal ghosts that haunt Hamlet.

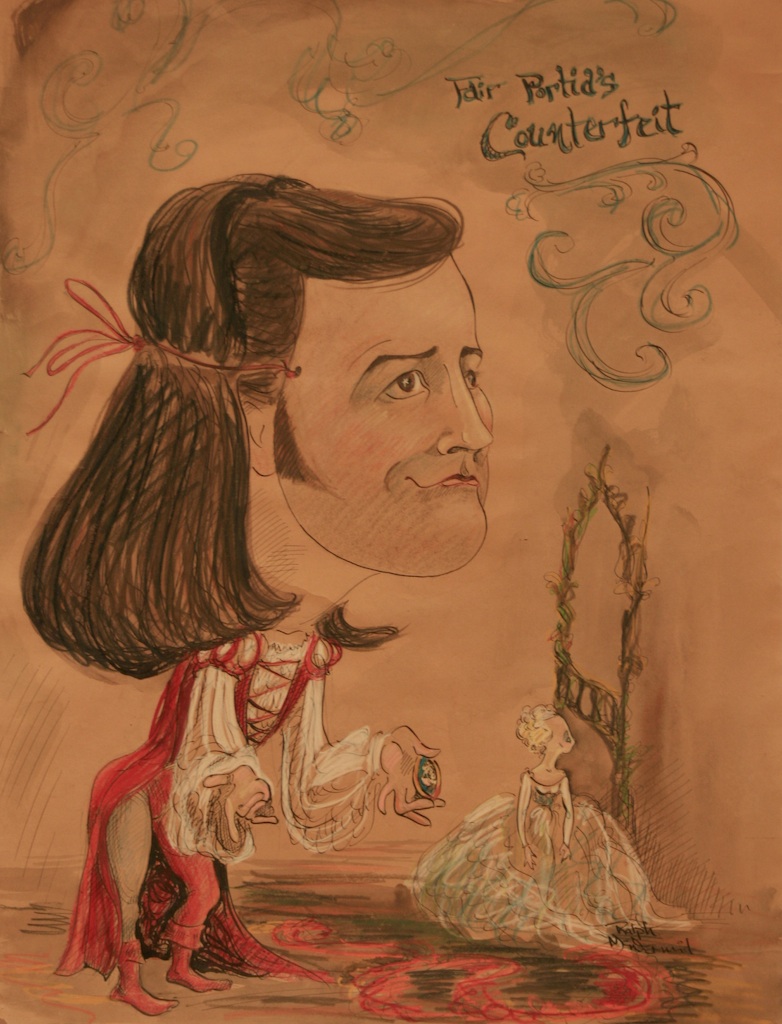

The gallery deliberately made it difficult to recognize the Shakespearean pieces commissioned specifically for the exhibit as compared with those not made with Shakespeare in mind. This interpretative problem speaks to the full spectrum of adaptation in visual arts–to what extent are unintentional resonances associated with Shakespeare’s iconic presence in contemporary Canadian culture always already present in the visual arts? Verne Harrison’s work, Sit on my Knee, Doll, takes one line from Henry IV and creates a deeply ironized self-portrait that becomes only apparent upon seeing the line spoken by Falstaff. Cheryl Ruddock’s Recovered Kelp, Lost Dress creates a portrait without a figure, thus exploring the reading of Ophelia’s suicide as a negation of female presence with a drawing of a dress and sea kelp but no human figure present except by inference.

The gallery deliberately made it difficult to recognize the Shakespearean pieces commissioned specifically for the exhibit as compared with those not made with Shakespeare in mind. This interpretative problem speaks to the full spectrum of adaptation in visual arts–to what extent are unintentional resonances associated with Shakespeare’s iconic presence in contemporary Canadian culture always already present in the visual arts? Verne Harrison’s work, Sit on my Knee, Doll, takes one line from Henry IV and creates a deeply ironized self-portrait that becomes only apparent upon seeing the line spoken by Falstaff. Cheryl Ruddock’s Recovered Kelp, Lost Dress creates a portrait without a figure, thus exploring the reading of Ophelia’s suicide as a negation of female presence with a drawing of a dress and sea kelp but no human figure present except by inference.

Introduction

The Stratford Festival was founded in 1953 by Tom Patterson. One of its most distinctive features of the Festival was its reinvention and use of the thruststage. Dating back to the Greek and Roman Amphitheatres and the Globe Theatre, for which William Shakespeare was a partner, the thrust stage had fallen into disuse in favour of the proscenium stage. The Stratford thrust stage was designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch and first appeared in the festival tent in the first season. Except for relatively small changes it remains relatively intact on the Festival stage today. Since its reinvention at Stratford, the thrust stage has been adopted around the world, including by the Royal Shakespeare Company in England.

The reason for the thrust stage’s renewed popularity lay in the flexibility and intensity of experience it provided for both the audience and the actors. This dynamic stage allows actors a much greater range of natural movement visible from much wider perspectives by the audience, a situation that makes performers rethink their use of space via their relationship to the audience as it sees them. Additionally; the audience sits around the stage, literally enclosing the actors, hence allowing for a more intimate setting than the proscenium stage. Due to the nature of the thrust stage and its improved visibility of all aspects of the production, costumes and props are enormously important, requiring more detail and specificity. The Stratford Festivals has a corps of highly skilled artisans that excel in wig making, shoemaking, leatherwork, metallurgy, costume decorating, and painting, as well as in making detailed and believable props, such as waxed fruit, robotronic monkeys, and royal, bejeweled crowns.

Introduction

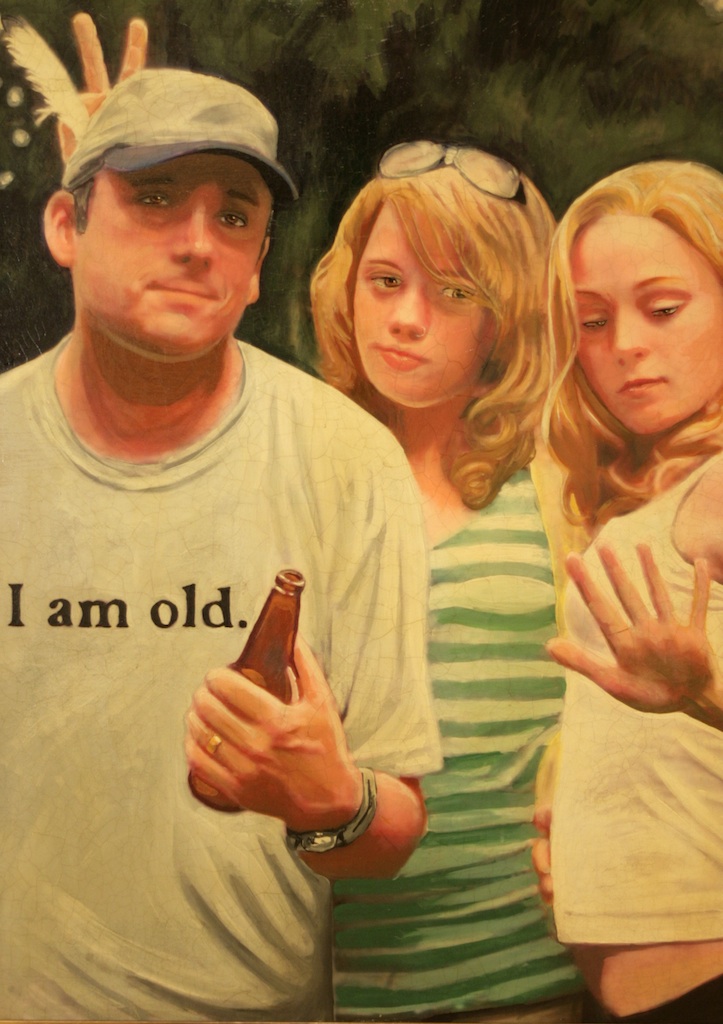

Two phenomena in the 1930s and 1940s contributed to the emergence of Shakespeare in French Canada. The first was the advent of radio and television, whose mandate of cultural enrichment brought the “masterpieces of world theatre,” including both English and French translated productions of Shakespeare. The second was the appearance of new theatre companies and playwrights who sought a modern alternative to traditional Québécois theatre. Throughout the 1960s, theatre was used in Québec as an affirmation of liberation and cultural independence. One such example is Robert Gurik’s 1968 production of Hamlet, prince du Québec, which, in a political allegory, plotted French and English political figures against each other. Using the iconic poet of British cultural authority was both symbolic and suggestive. In turning their backs on the likes of Racine and Molière, Québécois separated themselves from the French colonizers who had largely abandoned them. And in using Shakespeare to serve their own nationalist, linguistic, and cultural interests French Canadians asserted their freedom from anglicized Canada and anglophile colonial influences.

Two phenomena in the 1930s and 1940s contributed to the emergence of Shakespeare in French Canada. The first was the advent of radio and television, whose mandate of cultural enrichment brought the “masterpieces of world theatre,” including both English and French translated productions of Shakespeare. The second was the appearance of new theatre companies and playwrights who sought a modern alternative to traditional Québécois theatre. Throughout the 1960s, theatre was used in Québec as an affirmation of liberation and cultural independence. One such example is Robert Gurik’s 1968 production of Hamlet, prince du Québec, which, in a political allegory, plotted French and English political figures against each other. Using the iconic poet of British cultural authority was both symbolic and suggestive. In turning their backs on the likes of Racine and Molière, Québécois separated themselves from the French colonizers who had largely abandoned them. And in using Shakespeare to serve their own nationalist, linguistic, and cultural interests French Canadians asserted their freedom from anglicized Canada and anglophile colonial influences.

French Canadian adaptations of Shakespeare, especially early productions, have an extraordinary aesthetics often not seen in Shakespearean productions. This can be noted in Québécois artist Alfred Pellan’s costuming of Orsino and Olivia in the 1968 production of Nuit des rois, and the 1977 production photos of Jean-Pierre Ronfard’s King Lear, which utilized modern consumerism, and an obsession with money and sex to depict the story of Lear. This inventiveness, especially when it came to costume, sets, and musical scores can be attributed to a resistance to the conservative and traditional productions brought to Québec by English theatre and by the lack of aesthetic preconceptions about Shakespeare, so often indoctrinated into young actors and writers in English Canada.

This can be noted in Québécois artist Alfred Pellan’s costuming of Orsino and Olivia in the 1968 production of Nuit des rois, and the 1977 production photos of Jean-Pierre Ronfard’s King Lear, which utilized modern consumerism, and an obsession with money and sex to depict the story of Lear. This inventiveness, especially when it came to costume, sets, and musical scores can be attributed to a resistance to the conservative and traditional productions brought to Québec by English theatre and by the lack of aesthetic preconceptions about Shakespeare, so often indoctrinated into young actors and writers in English Canada.

Introduction

Not many would argue with the statement that William Shakespeare is the greatest and best-known English poet and dramatist. But who was the historical figure behind these timeless writings? What does the face of genius look like? For centuries, Shakespeare has continued to be elusive and shrouded in mystery. Of the many portraits and busts of Shakespeare, only two are accepted as authentic. One the copper engraving from the first Folio of Shakespeare’s work (1623) and the other, the stone memorial bust in Stratford-Upon-Avon. Both of these, however, were created after his death and the materials have deteriorated in quality. No paintings have definitively been proven to be of Shakespeare (painted during his lifetime), though a number of possible contenders exist. Of these, only the British-owned Chandos and the Canadian-owned Sander’s Portrait remain in serious contention.

The Sanders portrait was painted on two oak panels, which have been dated to 1597. The date “Anno 1603” appears in the upper right hand corner. If the painting is authenticated it will emerge as the only painting of Shakespeare to have been made during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The Sanders Portrait has been subjected to a wide range of scientific tests–perhaps more than any other Shakespeare painting–including radiocarbon analysis, infrared spectroscopy, materials tests, and X-rays, as well as expert analysis concerning style, techniques, hairstyles, and dress. All such tests have concluded that the Sanders Portrait dates from the general period (late Elizabethan, early Jacobean), and that the sitter is consistent with someone of Shakespeare’s age and social standing at that point in his career.

been subjected to a wide range of scientific tests–perhaps more than any other Shakespeare painting–including radiocarbon analysis, infrared spectroscopy, materials tests, and X-rays, as well as expert analysis concerning style, techniques, hairstyles, and dress. All such tests have concluded that the Sanders Portrait dates from the general period (late Elizabethan, early Jacobean), and that the sitter is consistent with someone of Shakespeare’s age and social standing at that point in his career.

Two elements, however, separate the Sander’s Portrait from other contenders. The first is a linen label affixed to the back of the portrait, this label now deteriorated to such a degree that it has been rendered unreadable, was legible in 1909, when the portrait was first tested for authenticity. It reads:

Shakspere

Born April 23-1564

Died April 23-1616

Aged 52

This Likeness taken 1603

Age at that time 39 yrs

This label and the glue that affixes it to the oak panels have been scientifically proven to date before 1640, making it a valuable piece of evidence. The second element is the portrait’s provenance: the Sanders Portrait has been passed from generation to generation in one continuous genealogy. Its current owner, Lloyd Sullivan, inherited it from his mother Kathleen Hales Sanders, who in turn had inherited the portrait through her family as it passed through the generations. This family provenance is an extraordinary story, entailing immigration, family dramas, fires, and any number of challenges that would make survival of such an object difficult.

Introduction

Adaptation is creative energy unleashed across a full spectrum of artistic possibility: from the most orthodox and conventional, the most slavish to the “original,” through to the most extreme and anarchic undoing in the name of artistic play and freedom.

Adaptation is creative energy unleashed across a full spectrum of artistic possibility: from the most orthodox and conventional, the most slavish to the “original,” through to the most extreme and anarchic undoing in the name of artistic play and freedom.

In Canada, this is particularly evident in relation to Shakespearean adaptation, which dates back to pre-Confederation and continues on in the present in myriad forms. Shakespearean referents have permeated into all aspects of Canadian popular culture and into all manners of theatrical production, from classical theatre through to community, fringe, school, and semi-professional theatre. Shakespearean adaptation is everywhere evident in Canadian mainstream culture, from CBC television comedy, such as the Royal Canadian Air Farce, and Wayne and Shuster, to theatrical productions that invoke Canada’s multicultural realities or references to Shakespeare found in popular music. Low budget, fringe, and local community productions are of significance to the spectrum of adaptation because they stretch boundaries and conventions and experiment to a degree not generally seen in mainstream theatre. Examples of this genre-bending experimental approach to Shakespeare are evidenced in cowboy-themed dinner theatre Shakespeare (Rodeo and Julie-ed), R&B adaptations in Night Clubs (Denmark and Elsinore), and rave-based fringe productions (Romeo/Juliet Remixed).

Adaptations have served as a vehicle to affirm mainstream stereotypical Canadian identity to both national and international audiences, evident in adaptations such as Ken Hudson’s hockey-based Henry V or Rick Moranis’s and Dave Thomas’s “hoser” Hamlet, Strange Brew. Additionally, adaptations in Canada have also served as a means to reclaim or affirm the identity and culture of minorities or oppressed groups, such as French-Canadians, First Nations peoples, and Afro-Canadians. Hamlet, Prince du Québec by Robert Gurik, Death of a Chief by Yvette Nolan, and Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet are notable examples of Shakespearean adaptations in Canada that explore specific communities within a broader Canadian context.

Adaptations have served as a vehicle to affirm mainstream stereotypical Canadian identity to both national and international audiences, evident in adaptations such as Ken Hudson’s hockey-based Henry V or Rick Moranis’s and Dave Thomas’s “hoser” Hamlet, Strange Brew. Additionally, adaptations in Canada have also served as a means to reclaim or affirm the identity and culture of minorities or oppressed groups, such as French-Canadians, First Nations peoples, and Afro-Canadians. Hamlet, Prince du Québec by Robert Gurik, Death of a Chief by Yvette Nolan, and Djanet Sears’s Harlem Duet are notable examples of Shakespearean adaptations in Canada that explore specific communities within a broader Canadian context.

Introduction

The Office of Opening Learning at the University of Guelph in conjunction with the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project established a school tour program, which ran the length of the Shakespeare-Made in Canada exhibit (a full six months). This program ushered in over 2000 students ranging in ages from kindergarten through to grade twelve. The school tour, for many students, was a first experience with an art gallery, theatre, or the word “adaptation.” Age-appropriate tours were designed to provide students with a basic understanding of Shakespeare, the definition of adaptation, and the relationship between Shakespeare and theatrical culture in Canada. Throughout the program, a focus was given to the refinement of knowledge and skills in visual arts, English, drama, history, math, and science through activities related to the objects in the various galleries.

The Office of Opening Learning at the University of Guelph in conjunction with the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project established a school tour program, which ran the length of the Shakespeare-Made in Canada exhibit (a full six months). This program ushered in over 2000 students ranging in ages from kindergarten through to grade twelve. The school tour, for many students, was a first experience with an art gallery, theatre, or the word “adaptation.” Age-appropriate tours were designed to provide students with a basic understanding of Shakespeare, the definition of adaptation, and the relationship between Shakespeare and theatrical culture in Canada. Throughout the program, a focus was given to the refinement of knowledge and skills in visual arts, English, drama, history, math, and science through activities related to the objects in the various galleries.

Included within the Shakespeare Learning Commons were scientific experiments on authenticating artwork, including x-ray spectroscopy and florescent examination, as well as an exploration of anamorphic art, a popular scientific method for creating perspective in paintings from Shakespeare’s period, which further situated Shakespeare in history and provided a science study component that was an alternative to the focus on drama and theatre in the rest of the Shakespeare Made in Canada exhibit. Additionally, adaptations and depictions of Shakespeare created by children, including drawings, figures and an extraordinary claymation adaptation of Romeo and Juliet by twelve-year old Jackson Mills situated adaptation in a more youth-oriented and accessible space. Visiting students were given the opportunity to try on costumes and recite well-known Shakespearean monologues, as well as play the literacy-based video game, Speare, created by the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project.

Included within the Shakespeare Learning Commons were scientific experiments on authenticating artwork, including x-ray spectroscopy and florescent examination, as well as an exploration of anamorphic art, a popular scientific method for creating perspective in paintings from Shakespeare’s period, which further situated Shakespeare in history and provided a science study component that was an alternative to the focus on drama and theatre in the rest of the Shakespeare Made in Canada exhibit. Additionally, adaptations and depictions of Shakespeare created by children, including drawings, figures and an extraordinary claymation adaptation of Romeo and Juliet by twelve-year old Jackson Mills situated adaptation in a more youth-oriented and accessible space. Visiting students were given the opportunity to try on costumes and recite well-known Shakespearean monologues, as well as play the literacy-based video game, Speare, created by the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project.