Introduction

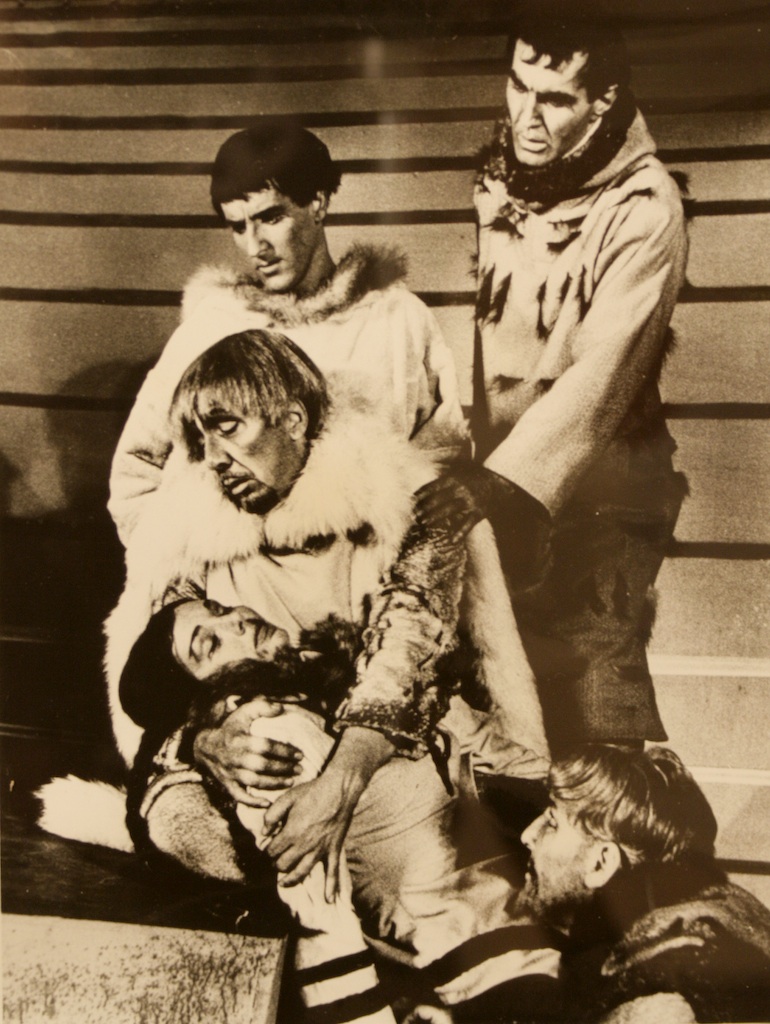

In 1961, theatre critic and designer Herbert Whittaker created a King Lear that took place not in Britain, but in the great white North of Canada under the guise of the “primitive society Canadians recognize best.” This “Eskimo Lear” took place in a time of new awareness and curiosity about First Nations peoples of Northern Canada, which in its own way heralded in an attempt to shed light on this largely unknown world. However, the blatant appropriation and misuse of visual images from another culture, which employed stereotypes and caricature rather than seeking the assistance of aboriginal actors or designers, reveals the legacy of colonial mentality that had already devastated aboriginal culture in Canada.

In 1961, theatre critic and designer Herbert Whittaker created a King Lear that took place not in Britain, but in the great white North of Canada under the guise of the “primitive society Canadians recognize best.” This “Eskimo Lear” took place in a time of new awareness and curiosity about First Nations peoples of Northern Canada, which in its own way heralded in an attempt to shed light on this largely unknown world. However, the blatant appropriation and misuse of visual images from another culture, which employed stereotypes and caricature rather than seeking the assistance of aboriginal actors or designers, reveals the legacy of colonial mentality that had already devastated aboriginal culture in Canada.

In 2002, Yvette Nolan, the artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts (NEPA), an aboriginal performing arts organization, found herself sitting on panels discussing diversity in Toronto theatre. Despite the multicultural environment of Toronto, theatres struggled to reflect this reality. It was here that the idea of producing an Aboriginal Julius Caesar sprang into her head, as she remarked, “it’s really just about band politics after all.” Native performers are rarely considered for roles in Shakespeare, and the fact that many native actors are not educated through formal schools or conservatories further puts them at a disadvantage. Yet as Nolan paired with Kennedy MacKinnon, a vocal coach and teacher of Shakespeare, to create a predominantly female production of Death of a Chief, they came to realize that Shakespeare resonates with almost everyone, and the themes of power, identity, community, and leadership within Julius Cesar can be paralleled with the realities of First Nations communities across Canada.

In order to confront present day issues, the collaborative team of actors, producers, and directors wrote about their own experiences and explored the stories from their traditions and how these resonated with aspects of Shakespeare’s version of the Caesar story. The history of First Nations peoples and Shakespearean texts in Canada has a long history of adaptations. Nicholas Flood Davin, a nineteenth century journalist (and the last person to “interview” Louis Riel), politician, and architect of the profoundly damaging Canadian residential school system, is a key figure in this history. Davin’s political views expressed in his Shakespearean adaptation, A Fair Grit, compounded the colonial imperative of the time, and utilized Shakespeare as a figurehead to privilege colonial culture over indigenous culture. Native Earth Performing Arts’ adaptation of Julius Caesar, by contrast, uses Shakespearean adaptation to reclaim First Nations culture by appropriating the tools of the colonizer, and thus represents a significant step in the emergence of a form of theatre that provides a space in which to initiate dialogue and healing about a devastating history of oppression and marginalization.

In order to confront present day issues, the collaborative team of actors, producers, and directors wrote about their own experiences and explored the stories from their traditions and how these resonated with aspects of Shakespeare’s version of the Caesar story. The history of First Nations peoples and Shakespearean texts in Canada has a long history of adaptations. Nicholas Flood Davin, a nineteenth century journalist (and the last person to “interview” Louis Riel), politician, and architect of the profoundly damaging Canadian residential school system, is a key figure in this history. Davin’s political views expressed in his Shakespearean adaptation, A Fair Grit, compounded the colonial imperative of the time, and utilized Shakespeare as a figurehead to privilege colonial culture over indigenous culture. Native Earth Performing Arts’ adaptation of Julius Caesar, by contrast, uses Shakespearean adaptation to reclaim First Nations culture by appropriating the tools of the colonizer, and thus represents a significant step in the emergence of a form of theatre that provides a space in which to initiate dialogue and healing about a devastating history of oppression and marginalization.

First Nations Image Gallery

Click here to return to the Introduction and here to view the Video Gallery

First Nations Video Gallery

Click here to return to the Introduction and here to view the Image Gallery